- Home

- Chris Lear

Running with the Buffaloes Page 6

Running with the Buffaloes Read online

Page 6

In creating the plan he works backwards from the NCAA’s to the summer base period. Each runner receives a copy of the plan, with most of the season’s workouts in place, in the summer. Sharing the plan with them at this early date ensures that they will know why they are doing what they are doing, and in turn, his athletes tend to buy into it.

The principles of aerobic development and periodization that he in-corporates in his “recipe,” as he calls it, are lessons learned from New Zealand coaching great Arthur Lydiard. What Lydiard discovered through trial and error over 30 years ago— that the development of one’s aerobic capacity is almost limitless (and almost universally underdeveloped by today’s coaches)—continues to be proven by exercise physiologists today.

Wetmore’s system is modified Lydiardism; he compromises Lydiard’s method to meet the unique demands of collegiate athletes looking to peak three times a year for NCAA’s. (In training Olympic champions like Peter Snell, Lydiard’s athletes competed in one 6 – 8 week season a year with a long-term goal of peaking in an Olympic year.) Wetmore has adapted Lydiard’s teachings to enable his athletes to race at a high level nine months a year. In the process, he is establishing a coaching legacy of his own.

Wetmore was introduced to Lydiard methods when he read his

book Running the Lydiard Way. He refers to it as a “foundational work”

RUNNING WITH THE BUFFALOES

25

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 26

whose principles “on many levels, are sound to this day.” Lydiard’s emphasis on long-term development with marathon training, coupled with his relentless development of an aerobic foundation, and his system of periodization are all concepts that Wetmore employs in designing his plan. Lydiard taught Wetmore two principal ideas:

1. Anaerobic and interval training is overrated.

2. You must continuously develop your aerobic capacity—and pick a time to run well.

This is Wetmore’s plan:

Period A: Ascending to Full Volume

The period lasts roughly six weeks, beginning when they resume training after taking a break at the end of outdoor track and lasting until the end of July. Each runner has a different goal volume depending on what he has done in the past. Wetmore recommends “no more than a ten percent increase from his last successful maximum volume.” In a letter he sent to the squad on June 24th, he wrote of this first period, “For the time being don’t attempt any hard workouts. No intervals; no ATs [Tempo runs]; no fartlek; no races. Just steady medium-distance runs and a weekly long run that is 20 percent of your total week. Get your bodies ready for the sustained volume of September and thereafter.”

Period B: Aerobic Short Specificity

This phase lasts five weeks and is characterized by work done at task pace (be that mile pace for milers during track season or 10k pace during cross country since that is the distance run at NCAA’s) that is not anaerobic. This means that another interval is not started until the athlete is fully recovered from the previous one. An example of a workout in this period is a fartlek with one minute on, four minutes off. There is a complete recovery between each hard effort so that no significant oxygen debt is accrued. This is mainly a transitional phase where Wetmore’s runners get used to going fast again.

Period C: Aerobic Long Specificity

This phase lasts six weeks and includes longer intervals than in Period B, while still avoiding anaerobic workouts. This phase is characterized by longer fartlek workouts, mile repeats, and long, hard aerobic efforts such as the ten-mile Dam Run. The rest between intervals will shorten towards the end of Period C as the runners advance their fitness. Because the intervals are much longer than in 26

CHRIS LEAR

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 27

Period B, his athletes start Period C running intervals at paces that are slightly slower than they will be running November 23rd. The paces drop over time. It is important to emphasize that through Period C the Sunday long run is emphasized, using the rule of thumb that it should be twenty percent of an athlete’s weekly volume. As a rule, the steady runs on Wednesday afternoons through this phase are fifteen percent of an athlete’s weekly volume.

Period D: Anaerobic Specificity

Now Wetmore introduces a heavy dose of traditional interval running: short, fast repeats with precious little recovery. The anaerobic work enables the runners to capitalize on the increase in their aerobic capacity while giving them what Lydiard calls “the vital edge” to race anaerobically. The Wednesday medium-distance run and the

Sunday run are continued as aerobic maintenance, the difference being that with only six weeks until Nationals, the distance of the runs will decrease by 10 to 25 percent. The pace of the medium distance and long runs remains steady.

Period E: Anaerobic Speed

The season’s last phase is marked by training sessions designed to induce deep anaerobic stimulus. In layman’s terms, this is when his runners puke and come back for more. The hard training sessions will include sprinting and intervals at paces substantially faster than race pace. The end result of these sessions is a feeling of sharpness—a power and fluidity of stride that causes a reversal of traditional mind-body communication. Up to now the mind is employed to overrule the unresponsiveness of the legs that is a result of the cumulative fatigue from an ungodly number of training sessions. Now it is the legs that start telling the mind: hey, you have the tools to raise some hell when it counts.

The Wolfe Influence

Wetmore’s training program demands a full investment from his athletes. He has expected nothing less from his athletes since he began his coaching career in 1972 as the coach and founder of the Edge City Track Club in Bernardsville, New Jersey. The Edge City Track Club begat the Mine Mountain Road Department, which led to an

assistant coaching position at Bernardsville High School.

The Edge City Track Club would never have existed had Wet-

more’s father not given him a copy of Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test in 1972. This book, says Wetmore, “blew my mind.” His RUNNING WITH THE BUFFALOES

27

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 28

father gave it to him as he was boarding a train to Massachusetts for a stint at Graham Junior College.

He read it cover to cover, finishing the text as he walked down Commonwealth Avenue towards his dormitory. Then, he sat down

on the steps of his dormitory, and read it again.

Reading this book was the beginning of his interest in ideas, in life, and in plans. From that day forward, there has never been a day when he has not been reading one or two books, ever.

Until this moment, his life lacked focus and direction. In fact, he was going to Graham after a short stint at TCU so he could study to be a TV journalist. Now, he set himself a new goal: “to read everything in the world!” with the aspiration of becoming an intellectual. “I was voracious after that,” he says. “I read 500 books in the next three years.”

Wolfe’s tale about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters capti-

vated Wetmore well after he finished the text. The hippies demonstrated to him the allure of living “on the periphery of existence.”

Wetmore took the lessons from their experiences and applied them to his coaching. He set about creating “an Edge City of physical well-ness, always with a purpose” where he and his athletes would “suffer as much as we can to see how good we can be, safety be

damned.” This ethic infuses his coaching to this day.

28

CHRIS LEAR

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 29

Sunday, August 23, 1998

Balch Gym

8 a.m.

Monster Island

Mark Wetmore moved to Boulder from Bernardsville, New Jersey, on August 17, 1991. Within “24 hours of moving to Boulder” he had discovered Magnolia Road. He was running it “prob

ably the first Sunday I was living in Boulder.” This was not by accident. He says, “Knowing where I am going to run is pretty important to me. I take the trouble to get a map, usually a topographical map, and I look for a squiggly wavy road. That usually means it is a little out of the way dirt road.”

Not many runners had discovered Magnolia Road then, and Wet-

more says, “the only person I saw up there in the first couple of months was Arturo.” Arturo is Arturo Barrios, the former 10,000-meter world record holder from Mexico who was then in the prime of his career.

Later that year he would take Bill Nann and Andy Biglow, two of his former protégés at Bernards High that were then running for CU, to run at Magnolia Road. Not once had they ever ventured there in three years at CU. A few days before interviewing for the position of volunteer assistant, Wetmore again went up to Magnolia Road and ran eight miles with Biglow and JD. “If I coach here,” he said to them, “you’ll be here every Sunday.”

Then CU Head Coach Jerry Quiller had been searching for a volunteer assistant coach to help with the distance runners. He was allowing his athletes to select their mentor from among several applicants for the position. Biglow had been campaigning for Wetmore to his teammates, but it was this run on Magnolia Road that convinced JD that Wetmore should be their coach. JD was on the selection committee that voted for Wetmore, and in 1992 Coach Quiller brought Wetmore on board.

His initial charges were the collectively disgruntled and underachiev-ing middle-distance runners on Quiller’s squad. JD epitomized the group.

A 1989 graduate of Campbell County High School in Gillette, Wyoming, he was the first schoolboy in Wyoming state history to run the mile under 4:20. He ran 4:13. An 800 meter in 1:51.67 was fast enough to garner him runner-up status at the prestigious Golden West Track and Field Invitational in Sacramento, California. Others in the group included Andy Samuelson, a miler from Colorado who ran 4:11 for 1600 meters at elevation to win his division at the Colorado state championships, and Mike Sobolik, a miler from Pueblo, Colorado. Alan Culpepper, a 3:50 high school 1500-meter runner from Texas, also fell under Wetmore’s charge.

Despite their top shelf credentials, neither Andy Samuelson nor JD

had qualified for a single conference final in four years. Each also had a RUNNING WITH THE BUFFALOES

29

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 30

full scholarship, along with Culpepper. None of the runners had ever made a Varsity cross-country team. They were dispirited and ready to try anything. Clearly, there was a lot of work to be done.

The first change Wetmore made was to add a long run to their program. Says JD, “Every Sunday morning we would do Mags.” They started by running twelve miles, and by the end of the fall, they were all running fourteen miles every Sunday at Magnolia Road. They accordingly upped their volume so that they were all running seventy to eighty miles per week. Their legs were tired and they were hurting.

With the exception of current US marathon star Scott Larson, who would run with the group at Mags on Sunday and do intervals with the Varsity cross country guys on Monday, the distance runners remained skeptical. After all, they were interval-trained athletes experiencing moderate success under Coach Quiller’s program. Any skepticism about Wetmore’s system vanished at the end of the cross country season when the cross country team left to run the NCAA regionals. The middle distance runners ran a 3000-meter time trial at Potts Field. JD recalls their performances: “I ran 8:35, a PR. Sobolik PR’ed. Samuelson PR’ed. Al [Culpepper] didn’t PR, but he ran 8:20 something. The distance guys were blown away. They gave in then [to Wetmore’s methods], although they were pretty desperate then

[to do well].” Culpepper’s performances particularly impressed the distance runners. Says current US Army runner and 1994 CU graduate Shawn Found,

“He [Wetmore] brought Culpepper back from the dead. By that winter he was running 13:53 for 5k in addition to his mile performances.”

The group’s success continued indoors. After having been the bane of the squad for their entire tenures, Wetmore’s runners finally contributed some points at the conference meet. All four men made the conference finals, and all four scored. Running the 1000 meters, the mile, and the 3000 meters, they scored more points than any other group on the team. JD PR’ed in the 1000 (2:26). Now the rest of the squad was really taking notice.

Found recalls witnessing the startling transformation of the middle-distance runners:

The reputation of the middle-distance guys was down the tubes. They were big guys scoring no points. They were running 4:10 in high school and 4:20

in college. In six months, he got them back running 4:05 again. He got Culpepper running 3:43 (for 1500 meters). We won Big Eight Cross without Wetmore, but by that spring the distance guys were getting spanked again. The middle-distance guys were scoring points and we were like “Shit, these guys are for real!”

Wetmore’s runners validated their indoor performance by again

making finals and scoring points at the outdoor Big Eight Conference meet. When all was said and done, all had PR’s. JD ran 3:51. Culpepper 30

CHRIS LEAR

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 31

ran 3:43. Sobolik PR’ed, and Andy Samuelson ran a 3:48 1500 meter—at elevation. In turn, their performances validated Wetmore. Found says, “It didn’t take long to know he knew his shit.”

Discouraged with his subpar performances, Found quit the team in the spring of 1993. Yet, the following summer saw Found also training under Wetmore. He recalls Wetmore telling him what he tells all his athletes: “It’s all or nothing. Give me two years, then you’ll start to see what’s going on.”

Found was hesitant at first. He says, “That’s hard to commit to.” But he did.

At the time Found was a self-described “semi-alcoholic complete zero.” He was fat, disillusioned, and working at 7-Eleven to make ends meet.

Found laughs as he recalls how Wetmore dropped by to see him at work one afternoon. He was on his hands and knees in the parking lot sweeping up broken glass when “all of a sudden I see some feet. ‘Can you tell me where the cliffs of Dover are?’” It was Wetmore. “Then he says, ‘Here’s the document. This station is temporary. See you in practice next week.’”

With that gesture, Wetmore won over Found. He sought out Found, and showed him in his typically understated manner that he cared about him. So Found went to work— hard. With Wetmore, there is no other way. Found says, “At the heart of it, and he’ll say it himself, he’s a martinet, a hard-ass. When you show up, you come to run. His methods are definitely Lydiardesque, and his temperament is like some hard-ass coach from the fifties. That’s the enigma of Mark, but that’s the appeal, too.”

Like the others, Found ran long and hard on Magnolia Road. Eight months later, a new runner emerged. “I won a conference title, set school records and got second in the 5k at NCAA’s indoors. Before that year, 14:17 was my best [5k]. I ran 13:51 at Indoor NCAA’s all because of Mark, all because he had me see long term.”

Furthermore, Found witnessed walk-ons enjoying as much success under Wetmore as those with sterling résumés. In the spring of 1994, Found was running a twenty miler on Magnolia Road while in 13:49 5k shape with Jay Cleckler and Jon Cooper, two Junior Varsity walk-ons. He was running a little over six minutes a mile, “and they blasted me. It was a preview of what they did that fall. Here were two guys from backwoods areas that no one wanted that became All-Americans. When they left they still couldn’t break 4:20 in the mile.”

The success of Cooper and Cleckler sent a message to all of Wetmore’s guys: It does not matter how little talent you have, if you follow his instructions and work hard, you will succeed. According to Found,

“ever since then, every Sunday run was a rumblefest.” Wetmore would tell his guys, “When you live on monster island, someone’s breathing fire every day.” Now everyone has their eye out for the next Coop

er or Cleckler, looking to see who is going to step up.

Last year it was current senior Matt Napier. A middle linebacker in RUNNING WITH THE BUFFALOES

31

Lear 012-059:Lear 012-059 1/5/11 1:22 PM Page 32

high school with fair 4:30ish track credentials, he was so large when he came to CU that Wetmore thought he still had more of a football physique than one suitable for running cross country. Napier was also married and had a child. With these commitments, Wetmore questioned his decision to run on the squad, but Napier would not be deterred.

“Trust me,” Napier told him, “it will be worth it.”

In his first season Napier ran only two races, finishing 31st in the Rocky Mountain Shootout and thirteenth at the Fort Hays State Invitational. His sophomore year he made greater strides, finishing 22nd at Big 12’s and 99th at NCAA’s. Last year the former linebacker finished eleventh at Big 12’s before earning his first All-American honors by finishing 39th at the NCAA’s. Napier is running Magnolia Road with the team this morning, and while he plans on redshirting the season, he stands as evidence to all the walk-ons that they, too, have a shot.

Wetmore did not speak to the younger guys yesterday, and the upperclassmen will not pull them aside and lecture them before today’s first run up Mags either. Says Goucher, “When it’s time to work, it’s time to work. They’ll find out on their own.”

But why make the effort to travel and run at 8000 feet when there are plenty of runs in Boulder? While there are “debatable physiological benefits” of going up to 8000 feet for the long run (Wetmore claims “the best thing would be to live there and train down here”), Wetmore’s primary motivation for running there is more pragmatic. They go there because “it’s a relatively quiet dirt road, the air is clear and it’s beautiful.”

Physiologically, he believes running on Magnolia Road offers his athletes the benefit of a “cardiopulmonary workout without hammering our legs because we’re going slower. They can run at the same heart rate up there as they would down here, and we’re not killing their legs.”

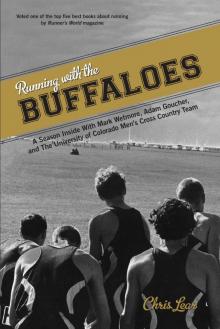

Running with the Buffaloes

Running with the Buffaloes